In September 2021, started the most destructive eruption of the last decades in the Canary Islands. During the 86 days that it lasted, 40 hectares of vineyard were lost, most of them hundreds of years old. One year after the disaster, we visited the island to assess its impact in the industry.

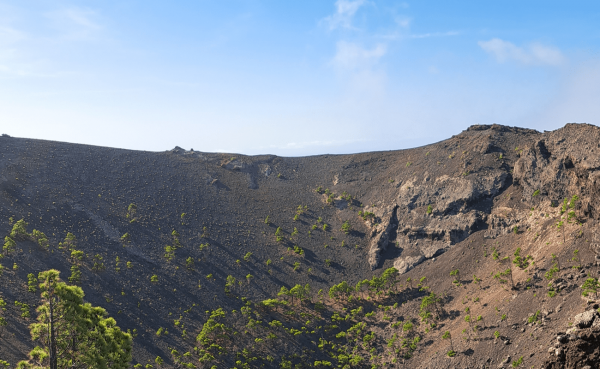

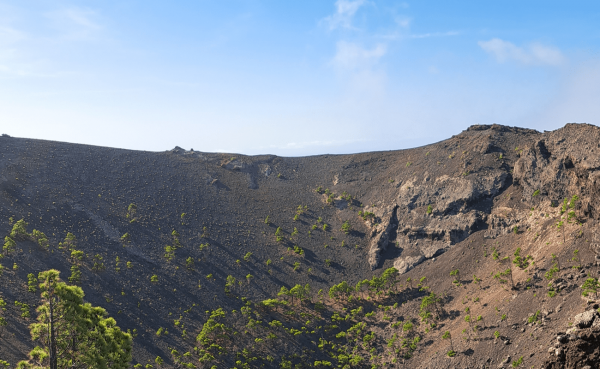

Born from the fire, La Palma is the most mountainous island in the Canary Island archipelago. With a surface of only 708,32 km, it hosted more than 7 active volcanoes since the 15th century and the steep slopes of the Caldera de Taburiente bring back memories of an even more agitated past before the historical records.

Viticulture arrived on the island shortly after the Spanish conquest, in 1493. As La Palma was one granted a monopoly in the Indian trade, together with Seville and Amberes, most ships stopped there in their route to the Americas, leading to a golden age for the wine industry. This became the main export of the island, specially the Malmsey wines produced in the volcanic soils south of the island. The other main producing region is located in the north, home of a unique wine aged in Tea barrels, an indigenous tree endemic to the island, that give the wine a resinous aftertaste similar to Retsina.

Previous image

Next image

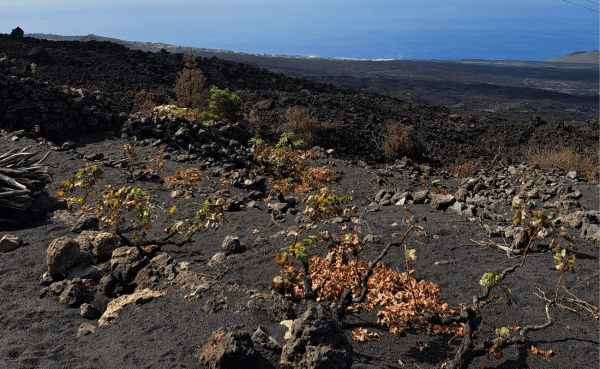

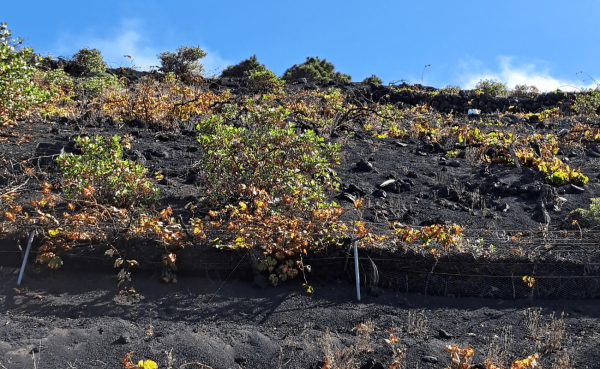

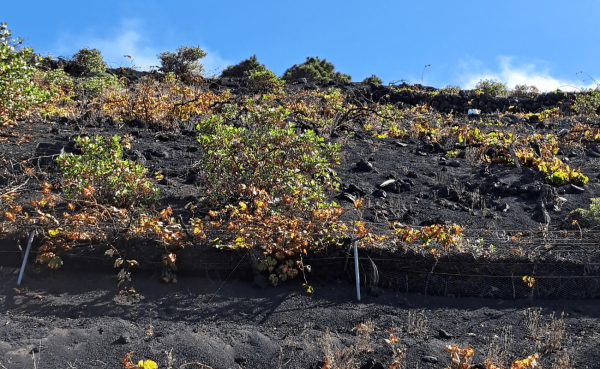

In the last decades, agriculture in the island has shifted to the production of bananas and vines have been confined to steep slopes and less fertile terrains. However, these vineyards are home of ungrafted varietals, some of them unknown, that only survived phylloxera in these remote locations. The black sands of its volcanoes preserved the ancestors of the first vines planted in Chile, Argentina, Mexico or California. The same volcanoes that in 2021 destroyed roughly 8% of the vine hectares of La Palma.

Almost a year has passed since the eruption of Cumbre Vieja and the scars it left on the island are still clearly visible.

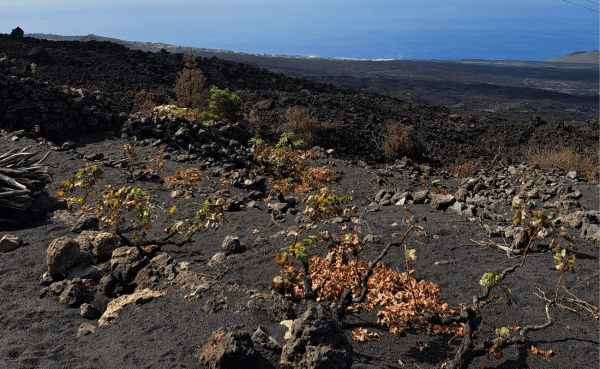

As of November of 2022, the ruins of houses and restaurants of southern Tazacorte give place to an endless landscape of barren land where the town of Todoque used to exist, cutting the island in half. One road ends abruptly before a gray flow of basalt that runs downs up to the sea. Following a narrow path we can see what remains of a vineyard. The vines stand defiant at a few meters from the basalt flow, unpruned and forgotten.

At Bodegas Teneguía the owner told us how they lived those dramatic days, when all their work of generations was at risk. Cut by a flow of lava to the west and with the eastern road closed due to the smoke and ashes, they were isolated from the rest of the island and their only way out was the sea. Contingency plans were drafted to evacuate all inhabitants by boat in case the magma flow changed direction further south or other volcanoes like the Teneguia showed any sign of activity. Luckily, none of these scenarios took place and the defiant vine terraces of southern La Palma are still at the same place they have been for centuries, in a lunar landscape of black sands trapped between the sea and the volcanic cones.

Previous image

Next image

The wineries from the northern part of the island remained unaffected by the eruption. Vines here are planted in terraces among the pine forests, wherever they find a hectare or two suitable for agriculture. Here, wildfires are a bigger threat than the lava. At Bodegas Vega Norte we were able to taste some of the Tea wines, while discussing the future of one of the lesser known wine regions of Spain. Here the wines are able to retain more acidity due to the cloud coverage and the cool winds compared with the southern cellars, so the wines from Negramoll, Malvasia or Gual shows a distinct personality, lighter and more refreshing. Wines made in Tea barrels are now made in very low quantities and the still reds and whites are currently the vast majority of the production.

Tourism and a long sailing tradition make it more likely for these wines to be found in the United Kingdom, Germany or the United States than in the restaurants of the island, most of them were out of local wine at the end of October 2022. In the big cities of Madrid or Barcelona is even more difficult to find these wines and most consumers associate Canary wines with Lanzarote or Tenerife, with a bigger production. But if La Palma, home of small wineries with low productions, will never be able to compete in volume, it is today a land of diversity and traditions, home of some of the oldest prephylloxeric vines of Spain and the last stronghold for varietals that are not planted elsewhere. A veritable treasure that was in danger of disappearing just one year ago.

In September 2021, started the most destructive eruption of the last decades in the Canary Islands. During the 86 days that it lasted, 40 hectares of vineyard were lost, most of them hundreds of years old. One year after the disaster, we visited the island to assess its impact in the industry.

Born from the fire, La Palma is the most mountainous island in the Canary Island archipelago. With a surface of only 708,32 km, it hosted more than 7 active volcanoes since the 15th century and the steep slopes of the Caldera de Taburiente bring back memories of an even more agitated past before the historical records.

Viticulture arrived on the island shortly after the Spanish conquest, in 1493. As La Palma was one granted a monopoly in the Indian trade, together with Seville and Amberes, most ships stopped there in their route to the Americas, leading to a golden age for the wine industry. This became the main export of the island, specially the Malmsey wines produced in the volcanic soils south of the island. The other main producing region is located in the north, home of a unique wine aged in Tea barrels, an indigenous tree endemic to the island, that give the wine a resinous aftertaste similar to Retsina.

Previous image

Next image

In the last decades, agriculture in the island has shifted to the production of bananas and vines have been confined to steep slopes and less fertile terrains. However, these vineyards are home of ungrafted varietals, some of them unknown, that only survived phylloxera in these remote locations. The black sands of its volcanoes preserved the ancestors of the first vines planted in Chile, Argentina, Mexico or California. The same volcanoes that in 2021 destroyed roughly 8% of the vine hectares of La Palma.

Almost a year has passed since the eruption of Cumbre Vieja and the scars it left on the island are still clearly visible.

As of November of 2022, the ruins of houses and restaurants of southern Tazacorte give place to an endless landscape of barren land where the town of Todoque used to exist, cutting the island in half. One road ends abruptly before a gray flow of basalt that runs downs up to the sea. Following a narrow path we can see what remains of a vineyard. The vines stand defiant at a few meters from the basalt flow, unpruned and forgotten.

At Bodegas Teneguía the owner told us how they lived those dramatic days, when all their work of generations was at risk. Cut by a flow of lava to the west and with the eastern road closed due to the smoke and ashes, they were isolated from the rest of the island and their only way out was the sea. Contingency plans were drafted to evacuate all inhabitants by boat in case the magma flow changed direction further south or other volcanoes like the Teneguia showed any sign of activity. Luckily, none of these scenarios took place and the defiant vine terraces of southern La Palma are still at the same place they have been for centuries, in a lunar landscape of black sands trapped between the sea and the volcanic cones.

Previous image

Next image

The wineries from the northern part of the island remained unaffected by the eruption. Vines here are planted in terraces among the pine forests, wherever they find a hectare or two suitable for agriculture. Here, wildfires are a bigger threat than the lava. At Bodegas Vega Norte we were able to taste some of the Tea wines, while discussing the future of one of the lesser known wine regions of Spain. Here the wines are able to retain more acidity due to the cloud coverage and the cool winds compared with the southern cellars, so the wines from Negramoll, Malvasia or Gual shows a distinct personality, lighter and more refreshing. Wines made in Tea barrels are now made in very low quantities and the still reds and whites are currently the vast majority of the production.

Tourism and a long sailing tradition make it more likely for these wines to be found in the United Kingdom, Germany or the United States than in the restaurants of the island, most of them were out of local wine at the end of October 2022. In the big cities of Madrid or Barcelona is even more difficult to find these wines and most consumers associate Canary wines with Lanzarote or Tenerife, with a bigger production. But if La Palma, home of small wineries with low productions, will never be able to compete in volume, it is today a land of diversity and traditions, home of some of the oldest prephylloxeric vines of Spain and the last stronghold for varietals that are not planted elsewhere. A veritable treasure that was in danger of disappearing just one year ago.